Hi, and welcome to this video on the First and Second Continental Congress of what would become the United States of America.

The First and Second Continental Congress was a meeting of delegates chosen from the thirteen colonies that first convened in 1774 and again in 1775 in Philadelphia. Today, we’ll look at the events which led up to these sessions, the goals, and achievements of each Congress.

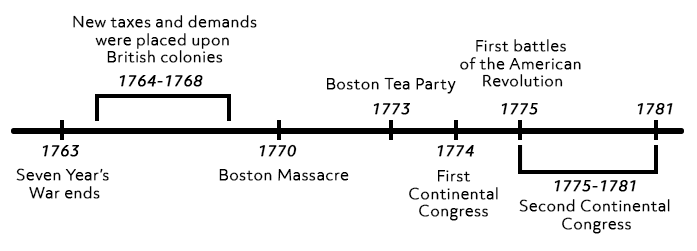

Timeline of Events

Before we dive in, let’s get our bearings during this eventful period.

The global Seven Years War came to an end in 1763. Over the succeeding five years, a series of new taxes and demands were placed upon British colonies in North America, which strained relations between the colonies and the motherland.

This led to unrest in Boston, and British soldiers were sent to restore order. This culminated in the Boston Massacre in March of 1770, in which five colonists were killed. In 1773, the cargo of a British ship was dumped into the Boston harbor in protest of the Tea Act.

The following year, punitive measures were passed by the British Parliament. The First Continental Congress came together that September. In April of 1775, the first battles of the American Revolution occurred. The Second Continental Congress came together the month after.

From 1775-1781, Congress oversaw the war effort, raised the Continental Army, made the Declaration of Independence, and drafted the Articles of Confederation. With the ratification of the articles, the Second Continental Congress became the Congress of the Confederation.

This timeline glosses over some details but gives you a general idea of the historical background. We start today’s topic with the aftermath of the Seven Years’ War.

Aftermath of the Seven Years’ War

The British government, seeking to recoup some of the war expenses from the thirteen colonies, passed the Sugar Act in 1764 and the Stamp Act in 1765, which angered the colonists. Resentment started to build up toward Britain in the colonies as more acts were put in place, eventually leading to events such as the Boston Massacre in 1770 and the Boston Tea Party in 1773.

In response, the British parliament passed a series of punitive measures against Massachusetts in 1774. These acts were known as the Coercive Acts in Britain and the Intolerable Acts in America. The laws had the opposite effect intended and prompted the colonies to cooperate with each other.

On September 5th, 1774, 56 delegates from 12 of the 13 colonies met in Carpenters Hall in Philadelphia (Georgia was not involved initially as they needed British soldiers to help ward off Native American advances). The delegates for each state were chosen by the people, the colonial government, or by correspondence committees and included two future US presidents, John Adams of Massachusetts and George Washington of Virginia.

First Continental Congress

There was not a set agenda, so the first sessions were dedicated to discussing what course of action should be taken against Britain. There were differences of opinion. Some delegates wished to reestablish cordial relations with Great Britain, while others believed in greater autonomy. Joseph Galloway, a Pennsylvanian delegate, proposed a Plan of Union of Great Britain and the Colonies, which advocated the establishment of a political union with Britain and the formation of an American legislative body. The plan was supported by many delegates, but in the end, only five colonies supported it, with six opposed. In October, the Declaration and Resolves of the First Continental Congress was issued as a statement of common principles along with a plan to boycott British goods.

The Congress adjourned in October, agreeing to meet again in 1775 if the disputes were not resolved. Before the Second Continental Congress could convene, the first shots of the American Revolution were fired at Lexington and Concord on April 19th, 1775.

Second Continental Congress

In May of that same year, the Second Continental Congress convened in Philadelphia. The agenda for this meeting altered quite dramatically as a result of the events in Boston. Rather than coordinate a boycott, the Congress found itself with a war effort to organize against Britain. On June 14th, a Continental Army was authorized, and George Washington was appointed its commander two days later.

Despite these developments, a significant portion of the Congress favored avoiding war and reconciling with Britain. Many still considered themselves loyal British subjects and desired to change the nature of the relationship with Britain rather than sever it. Others saw war and separation inevitable but were not yet convinced there was enough popular support for independence.

The Olive Branch Proposal

An attempt to avoid war, known as the Olive Branch Proposal, was approved in July and reached London by September. But King George III had already declared the colonies to be in a state of rebellion on August 23rd. According to the American delegates sent to deliver the proposal, the king never even looked at it. With the hopes of peace dashed, support for independence grew.

Common Sense

By the turn of the year, a pamphlet written by Thomas Paine called Common Sense made a strong case for independence and was widely distributed throughout the colonies. There was a question of whether the Second Continental Congress actually possessed the authority to declare independence. While taking on the appearance of a government, the Congress could not overrule local Colonial Assemblies or levy taxes.

The Remainder of the Revolution

The Continental Congress was more of a revolutionary committee than a central government. The Congress could declare war and negotiate with foreign powers (in fact, Benjamin Franklin was sent to France in 1776 to gain support), but was greatly limited in its capacity to raise funds or impose laws upon individual states. The delegates present were bound by the will of the Colonial Assemblies, and it was only when a majority of the states supported independence that a declaration could be made. After lengthy debates over the language, the declaration was approved on July 2nd and finalized two days later.

The latter half of 1776 was a difficult time for the revolution; Washington’s army suffered a succession of defeats and was nearly wiped out. After a morale-boosting victory in December 1776, a measure to extend the enlistment of the soldiers from 12 months to three years or the war’s end was passed to keep the army in the field. The tide of the revolution began to turn in 1777 with the loss of a British Army in Saratoga and the intervention of France, Spain, and the Netherlands in 1778.

The Articles of Confederation were drafted by a committee around the same time as the Declaration of Independence in order to establish a formal union of the states. There was a lengthy debate over what form the government should take. By November 1777, the final version was approved and sent to individual states for ratification. Maryland was the final state to ratify on February 2, 1781. With the passage of the Articles of Confederation, the Second Continental Congress became the Congress of the Confederation.

The term ‘Continental Congress’ was still widely used; the new congress was largely an extension of the old. There was a great deal still to do before the government of the United States would assume the form we recognize today, but that is a topic for another video. The First and Second Continental Congress did not create a central government of the colonies but did lay the foundations for the United States of America.

Review

1. Where did the First and Second Continental Congress meet?

- New York

- Boston

- Philadelphia

- Savannah

2. Both the First and Second Continental Congress met in Philadelphia, though the Congress was forced to relocate to Baltimore when Philadelphia was captured.

Which of the following powers did the Second Continental Congress NOT have?

- Raise an army

- Raise taxes

- Negotiate with foreign powers

- Declare war

Thanks for watching, and happy studying!