Hello! Welcome to this video on multicultural counseling.

In this overview, we’ll begin by examining multicultural counseling and social identity through the lens of intersectionality. We will then explore the following concepts:

- Discrimination and prejudice

- Privilege and oppression

- Cultural responsiveness

- Cultural humility

- Professional guidelines and ethical standards

We’re going to be defining a lot of terms in this video, so feel free to pause, take notes, do whatever you need to.

All right, let’s get started.

What is Multicultural Counseling?

Multicultural counseling is any therapeutic service that considers multiple dimensions of a client’s sociocultural identity. Sociocultural identity is determined by a person’s simultaneous membership in various social groups. These group affiliations contribute to how individuals view themselves and how they are viewed by society. Compositional elements of sociocultural identity include:

- Race

- Ethnicity

- Age

- Spirituality and religion

- Mental and physical abilities

- Marital status

- Neurodiversity

- Weight and size

- Education

- Nationality

- Sexual orientation

- Immigration status

- Gender

- Gender identity and expression

- Socioeconomic background

- Political affiliation

Many aspects of personal identity are grounded in social constructs, which change over time as they are influenced by sociopolitical factors, cultural norms, collective beliefs, and social interactions. The meaning or value placed upon certain aspects of social identity and their alignment with societal norms vary across cultures. Some aspects of social identity are influenced by a person’s biology and psychosocial development, while others are impacted by environmental changes and life experiences. Thus, elements of a person’s sociocultural identity are complex, transient, and fluid.

Intersectionality

Counselors commonly use an intersectional approach when conducting multicultural counseling. Intersectionality considers the full range of each individual’s sociocultural identity. It focuses on the ways in which interconnected elements converge to create unique worldviews and sociocultural experiences.

In 1989, Kimberlé Crenshaw introduced the term intersectionality to describe societal inequities and discrimination toward black women. Crenshaw argued that discrimination toward black women cannot be viewed as solely racist or sexist. Instead, it is the intersection of both identities that creates structural inequities for black women as a group. Crenshaw proved that the ways in which each aspect of social identity intersects and overlaps are significant—that a person’s sociocultural identity is more than just the sum of its parts.

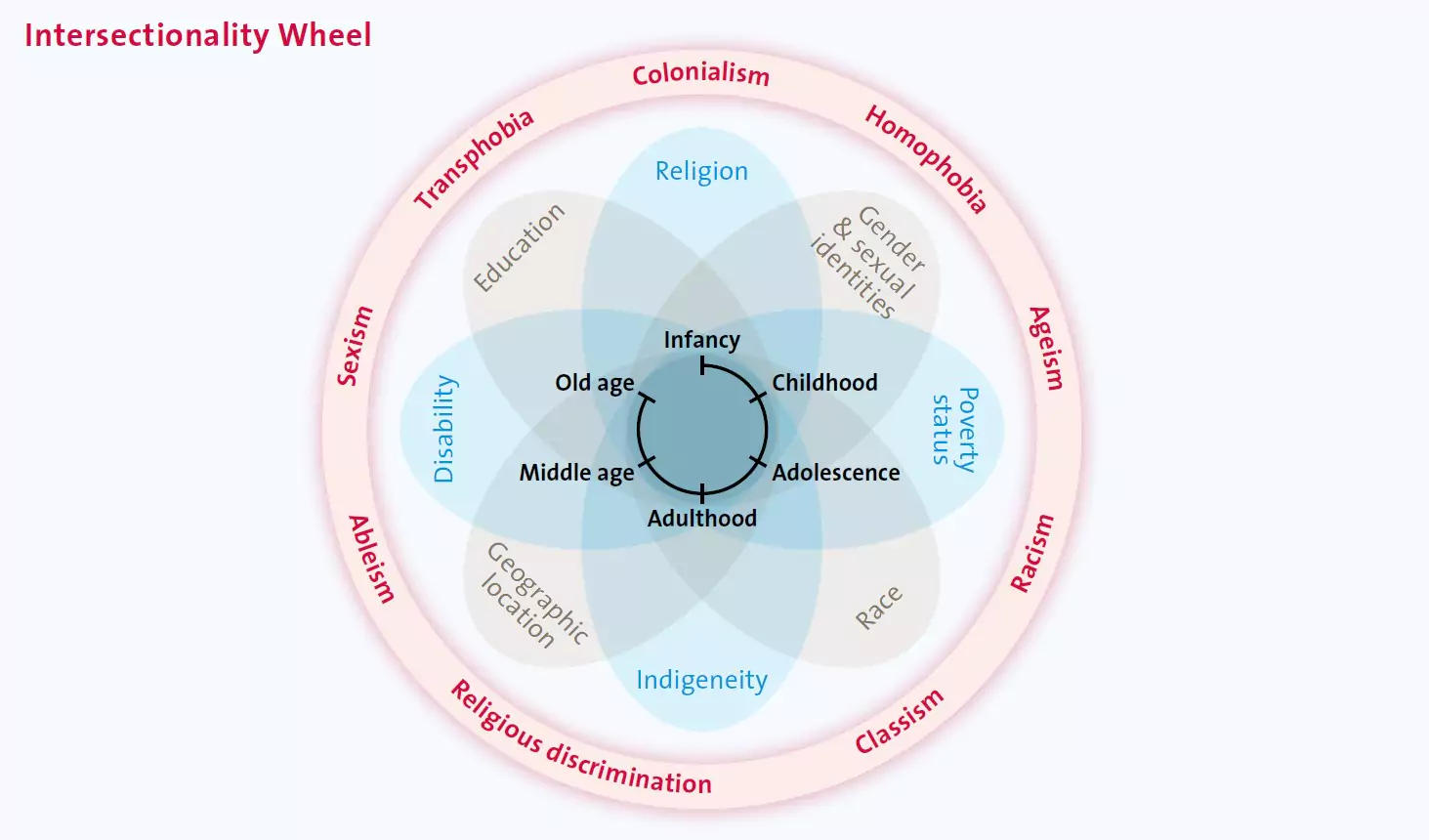

This image captures the overlapping dimensions of intersectionality:

You’ll notice the superimposed dimensions of human development in the center of the circle. Moving out from the core are elements of sociocultural identity. The outer layers show various forms of discrimination experienced by intersectionally marginalized populations.

Let’s closely examine some components of intersectionality, beginning with discrimination.

Discrimination

Discrimination is the unjust and differential treatment toward individuals based on their actual or perceived social groupings. It arises from variables that undercut social justice, diversity, equity, and inclusion. Discrimination is driven by prejudice, which is defined as negative, irrational, or unjustified attitudes and beliefs toward another social group.

Discrimination excludes and relegates non-dominant social groups to the outskirts of society through marginalization. Individuals in intersectionally marginalized communities experience mental health disparities due to inequitable access to social, economic, occupational, and educational resources. Discrimination can be manifested in overt and covert forms.

Structural racism and microaggressions are examples of covert forms of discrimination. Structural racism refers to conditions that create, condone, and perpetuate racism through institutional laws, policies, and practices. Examples of structural racism include residential segregation, biased criminal sentencing, and voter suppression. **Microaggressions** are negative and derogatory slights, insults, or comments targeting intersectionally marginalized groups (e.g., telling a racist joke or making a homophobic social media post). There is strong empirical evidence showing that the collective toll of microaggressions has a profound and detrimental effect on a person’s physical and psychological health.

Privilege

Intersectionality examines how interlocking systems of oppression create inequities through the use of power. The inequitable distribution of power is known as privilege. Privilege provides individuals with unearned rights, opportunities, and immunities solely based on their social group membership. Privileged groups define societal norms, values, beliefs, and expectations, and they seek to maintain the status quo.

Oppression

Oppression occurs when a privileged subgroup has differential access to power, wealth, and status and uses it to control, prolong, or enable inequities. Individuals experiencing oppression are at an increased risk for behavioral health disorders. They are also more likely to experience poorer outcomes due to disparities in healthcare access, utilization, and the quality of care received.

The Role of Culturally Responsive Counselors

Now that we have a better understanding of intersectionality, let’s look at the role of the culturally responsive counselor.

Culturally responsive counselors understand the significance of their own cultural identities on the client-counselor relationship. Through the lens of intersectionality, counselors recognize that individuals holding multiple intersecting and oppressed identities face unique experiences of harassment, stigma, and discrimination.

Thus, the role of the culturally responsive counselor is twofold:

Second, the influence of the counselor’s sociocultural identity must also be acknowledged, as it has a direct and substantial impact on the therapeutic alliance. This process involves introspection, self-examination, and recognizing implicit biases.

Implicit biases are subconscious attitudes, stereotypes, and assumptions affecting everyday actions and decision-making. Implicit biases originate from schemas, which are mental shortcuts developed in childhood to help people understand and predict the world. These mental shortcuts quickly evaluate, categorize, and classify information, resulting in hidden assumptions and implicit biases. These biases are often reflected in microaggressions.

The American Psychological Association’s inclusive language guide provides culturally appropriate definitions and terminology to help avoid microaggressions in conversation and writing. Contemporary alternatives to problematic language are provided, enabling counselors to honor and validate the ways in which clients self-identify. Using contemporary alternatives, including person-first language, helps create an environment where clients feel seen, heard, valued, and respected.

Culturally responsive counselors acknowledge and examine their own implicit biases through the practice of cultural humility. Cultural humility is the life-long process of self-reflection, self-critique, and introspection. It is a strong foundation for culturally reflexive practices by recognizing and mitigating power imbalances within the client-counselor relationship. Cultural humility allows counselors to recognize the influence of stereotypes, biases, and assumptions.

Culturally responsive counselors are aware of systemic issues and the impact of historical events. As a result, counselors understand and validate experiences of oppression-based stress and trauma. The commitment to providing culturally and linguistically appropriate care also extends to understanding the values, beliefs, customs, gender roles, family systems, and communication styles of diverse cultures.

Tripartite Model of Multicultural Competencies

In the early 1980s, Derald Wing Sue, a pioneer in multicultural counseling, developed the tripartite model of multicultural competencies, which is still used today. This model measures a counselor’s multicultural knowledge, skills, and awareness. The Multicultural and Social Justice Counseling Competencies (MSJCC) has since expanded on Sue’s tripartite model by adding actionable elements of social justice and incorporating principles of cultural humility. The MSJCC’s framework encourages counselors to recognize the influence of their biases, worldviews, and assumptions as members of intersectionally marginalized and privileged groups, as well as the advantages and disadvantages each membership affords.

The APA’s multicultural guidelines stress the importance of:

- Viewing cultural identity through multiple fluid and complex social contexts

- Understanding the role of diverse environments as social determinants of health

- Moving beyond personal biases, stereotypes, and categorical assumptions

- Understanding the role of diverse languages and communication

- Providing strengths-based and culturally-adaptive treatment

- Adapting an international and biosociocultural context

- Attending to past and present experiences with power and oppression

Counselors are ethically obligated to address systemic barriers through advocacy at individual, institutional, structural, and group levels. The ACA’s Advocacy Competencies underscore the importance of advocacy in collaboration with and on behalf of individuals, groups, systems, or communities to strengthen counselors’ commitment to social justice. The National Board for Certified Counselors’ Code of Ethics includes advocacy as a core counseling value and belief, encouraging counselors to advocate for access, equity, and expanding resources in underserved populations.

The National Association of Social Work’s Code of Ethics reflects an updated standard (Standard 1.05) for cultural competence. The word demonstrate is now added, stating social workers are to “demonstrate” culturally informed knowledge, understanding, awareness, and skills. Social workers are also charged with acknowledging personal privilege and standing against racism, oppression, and discrimination. Subsection (c) was also added to Standard 1.05, stating:

That brings us to the end of our discussion today. We did cover a lot of information and defined a lot of terms, but remember that it’s important to frequently check for updated policies, standards, and procedures mandated by professional boards and other official entities. I hope this video was helpful.

Thanks for watching, and happy studying!