The term “Manifest Destiny,” coined in a partisan newspaper in 1845, became synonymous with the ambition and scope of American territorial expansionism. By the 1840s, that urge of expansion had made major strides. The doctrine of Manifest Destiny led the United States into war with Mexico, with Native-American tribes populating the country’s western territories, and eventually with Spain for control of overseas colonial possessions.

Territorial Expansion and Jefferson’s Vision

The concept of the United States having a Manifest Destiny to expand in size westward across the North-American continent was a long-standing fascination dating back to the founding of the country. But it was more than just territorial enlargement. Under Manifest Destiny, territorial enlargement was necessary because of the exceptionalism of the US as a quasi-democratic society and defender of liberties.

As for a material beginning of Manifest Destiny, we can look back to 1803 when Thomas Jefferson inked the Louisiana Purchase with Napoleon, doubling the territory of the US overnight.

President Jefferson was committed to using the gains to build what he called an “empire of liberty” with western settlers, whom he envisioned as self-sufficient farmers upholding the ideals on which the country was founded. The territorial ambitions of the westward-looking policy expansion received energetic support from Andrew Jackson, who invaded Florida in 1818, with the resulting Adams-Onis Treaty bringing that territory into the US and also laying an official American claim to the Oregon Country in the Pacific Northwest.

Manifest Destiny and Religious Influences

The concept of Manifest Destiny was gaining traction – and moral strength from religious influences. It was widely believed by proponents that Americans were chosen by God to expand their republic from the shores of the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean. Americans, so the thinking went, had an obligation to expand the size and global power of their country to extend the benefits of their moral mission to as many people as possible.

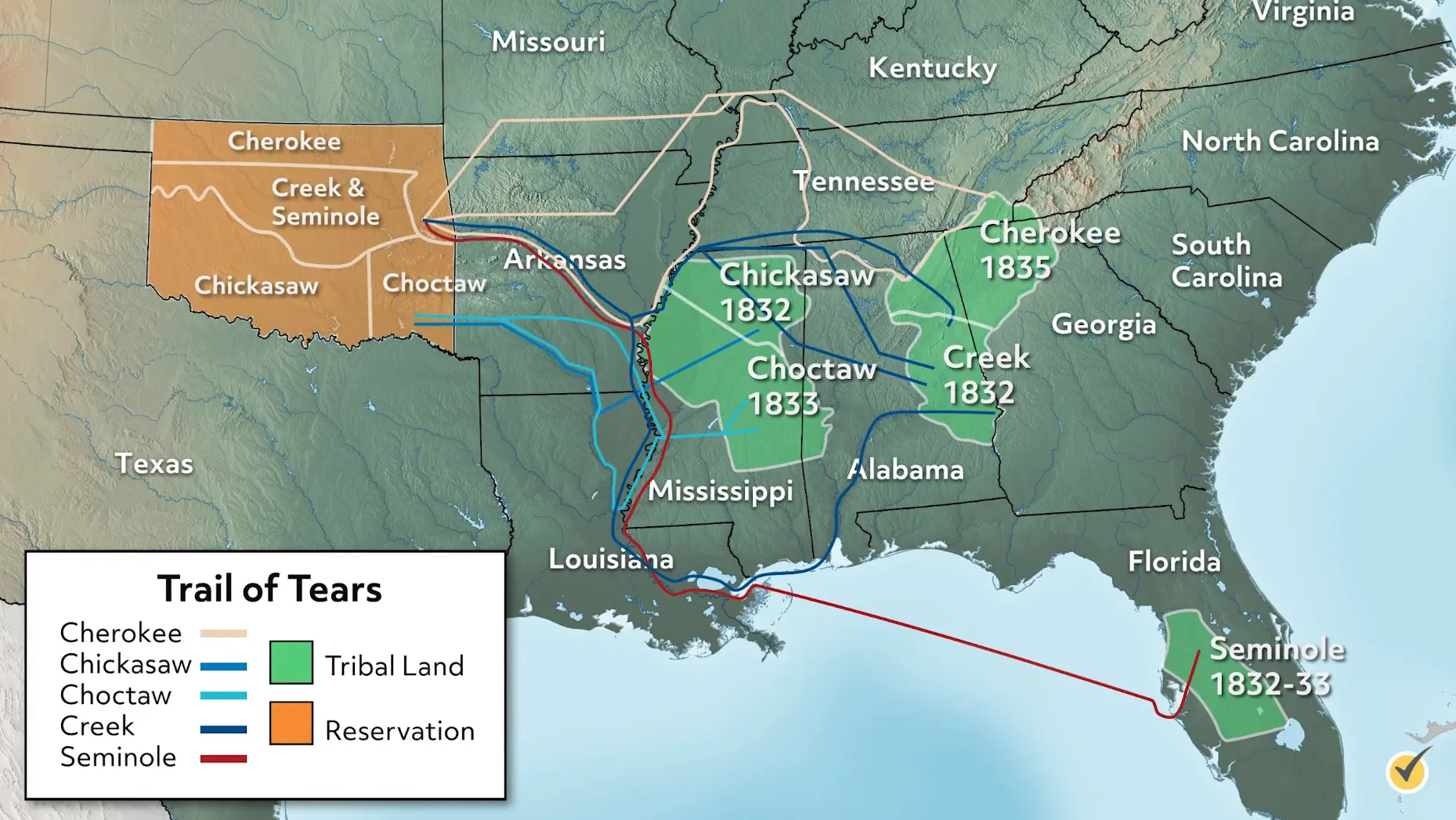

President Jackson also oversaw massive American settlement of southern and southeastern territories that displaced Native-American tribes, who were forced to sign their lands over to the US and relocate west of the Mississippi River, under what became known as the Trail of Tears.

This treatment of indigenous peoples sparked occasional outbursts of sympathy from certain sectors of the American population, but the calls for land grabs were getting louder. The narrow-minded outlook of a supposedly universalist Manifest Destiny continued to create contradictions, especially in US relations with its southwestern neighbor Mexico, which had become independent from Spain in 1821.

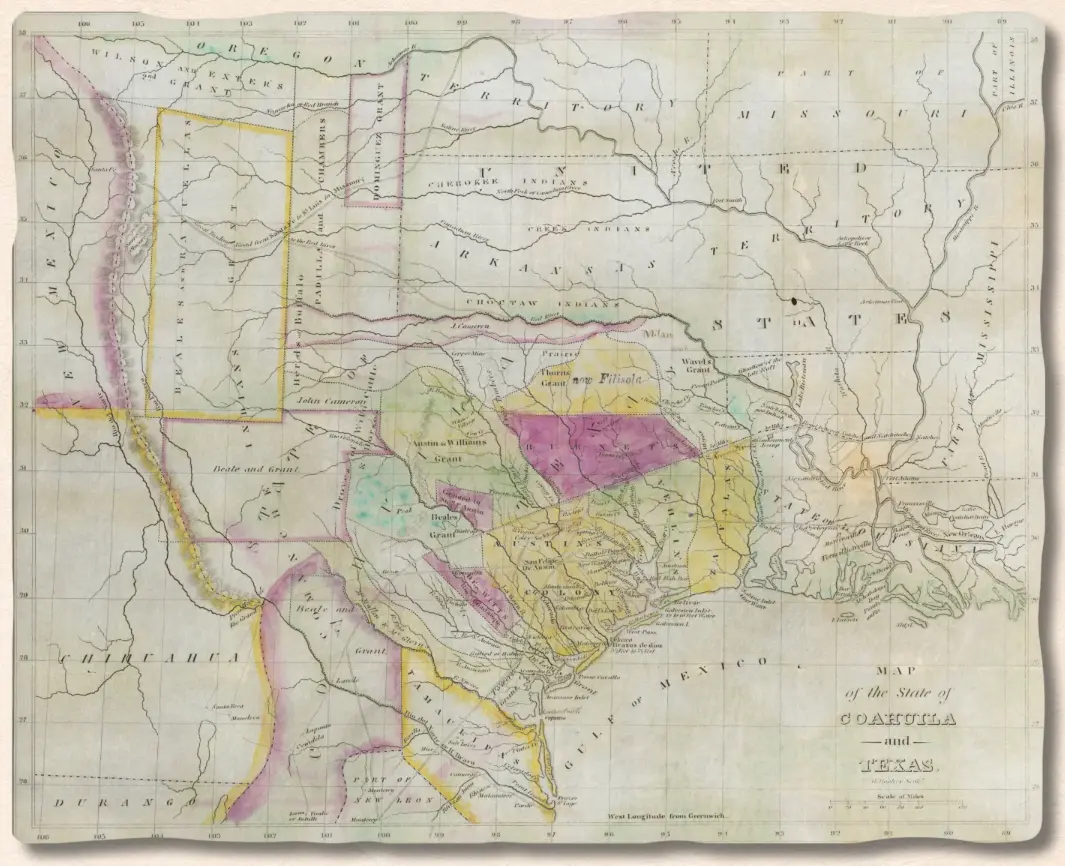

The Mexican government had encouraged settlement by individuals in its territory of Texas, using land grants and American settlers soon came flooding in. However, these American immigrants repaid their Mexican benefactors not with gratitude but with contempt, as they began openly defying Mexican authority. It all erupted into violence in the early 1830s, with American Texans declaring their independence from Mexico in 1836.

Shortly after taking office in 1845, President Polk negotiated 49 degrees north latitude as the border between American Oregon territory and British Canada, comprising the states of Washington, Oregon, Idaho, and parts of Wyoming and Montana. And the next prize was Mexico’s territory to the west of Texas.

As a deliberate provocation, in June 1845, Polk sent a force under Zachary Taylor ostensibly to defend American settlers in Texas, but really to seek a pretext to spark war for more Mexican lands. He even told commanders of the US Pacific naval fleet to seize Californian ports preemptively if war erupted. Taylor’s troops marched 150 miles south of the Nueces River—the traditional Texas-Mexico border—all the way to the Rio Grande, in essence invading Mexico. Justifiably, the Mexican army attacked Taylor’s force near the Rio Grande—and President Polk then had the pretext for armed conflict he wanted. The US went to war with Mexico in May 1846.

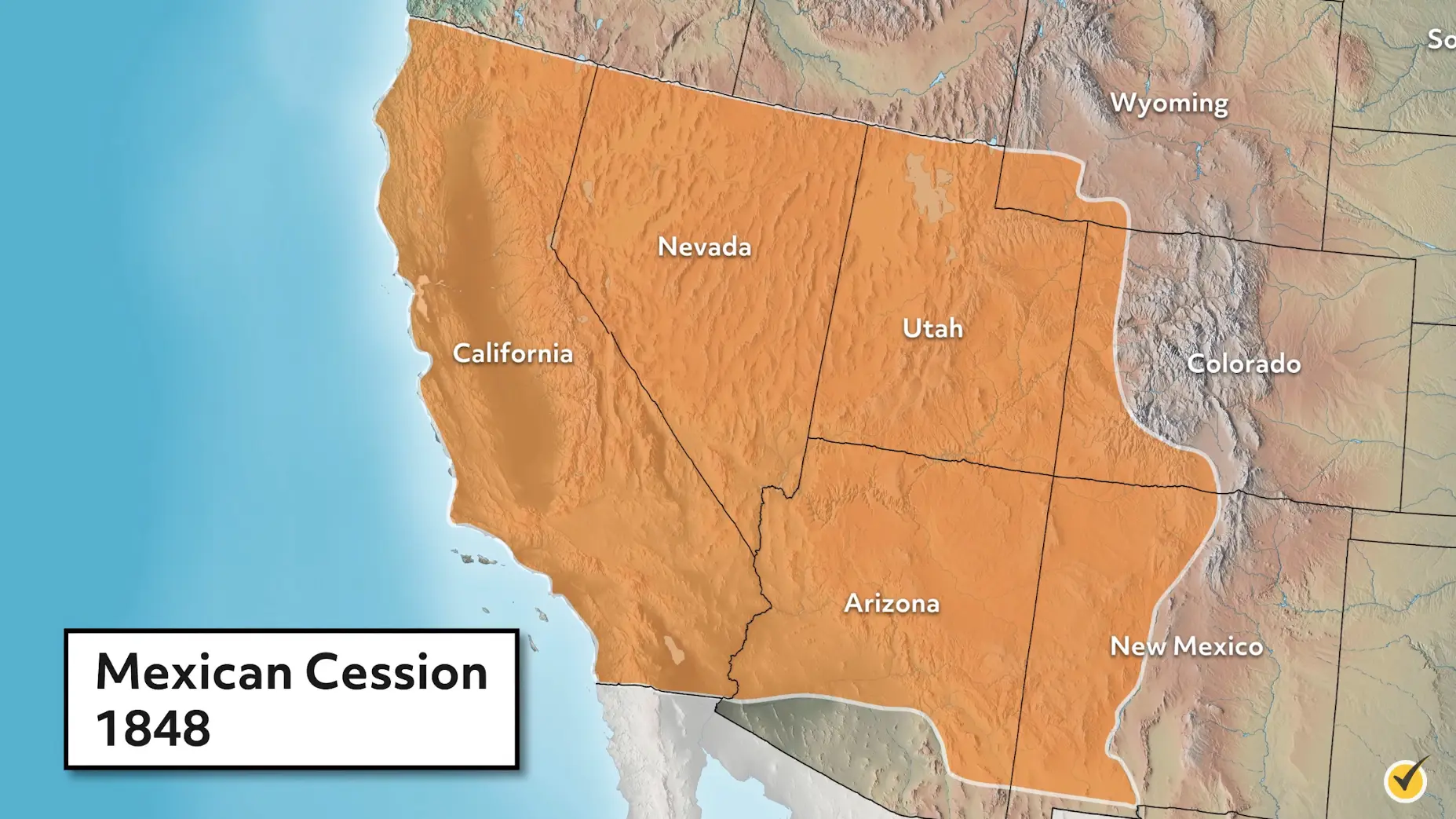

The fighting lasted roughly two years and led to the US taking vast territories from Mexico in the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848.

In that treaty, the US agreed to pay $15 million worth of damages to the Mexicans. Also in the treaty, Mexico renounced its claim to Texas and was deprived of territories that would become part of the states of New Mexico, Colorado, Arizona, Nevada, Wyoming, Utah, and California. With the American claim to territory in the Oregon Country already resolved and the Gadsen Purchase of 1853 adding southern territory to Arizona and New Mexico, the United States had opened up enormous tracts of land for settlement.

The underside of the bountiful land and freedoms promised by Manifest Destiny was large-scale plundering of wealth and territories controlled by “foreigners,” the very same Native Americans and Mexicans who were the original inhabitants of the lands conquered under the expansionist program.

Criticisms of Manifest Destiny

Harsh critics were on the scene from the very outset, among them a young politician named Abraham Lincoln, then establishing his status as an Illinois congressman. After hostilities in the Mexican-American War began in 1846, Lincoln emphatically pointed out that President Polk had “…unnecessarily and unconstitutionally commenced a war with Mexico.” Later, General Ulysses S. Grant, one of Lincoln’s most effective military commanders in the Civil War, would call the Mexican-American War “the most unjust war ever undertaken by a stronger nation against a weaker one.”

When Americans began moving in large numbers to the so-called “Far West” in the 1840s, the contradictions inherent in Manifest Destiny exploded even more. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo put roughly 100,000 Mexicans under US jurisdiction. More than 300,000 Native Americans, meanwhile, were already resident on the lands gained through the Louisiana Purchase and the Mexican-American War. The Anglo-Saxon, Protestant overtones of Manifest Destiny posited that Native Americans and Mexicans needed to be shoved out of the way.

Violent warfare with these populations was the result. After the Civil War, it reached a frenzy, when the army was able to concentrate its full efforts on “winning the West.” In reality, this meant hunting down and even committing genocide against Native Americans. The Battle of Wounded Knee in December 1890, in South Dakota – also called the Massacre of Wounded Knee – marked the end of this series of wars under the Manifest-Destiny banner. US troops murdered roughly 300 Lakota, mostly women and children. The sway of the once-mighty Native-American tribes was in ruins, and one era of Manifest Destiny was over.

It made a brief revival in the 1890s, with the US taking aim at Cuba and managing to take Puerto Rico, the Philippines, Guam, and Hawaii, though the Philippines later revolted and became recognized as an independent nation after World War II.

Review Question

Ok, we’ve covered a lot in this video, so let’s look at a review question before we go to see what you can remember:

All of the following were instances of support for American territorial expansion under Manifest Destiny except

- James K. Polk’s 1844 presidential campaign

- Herman Melville’s 1850 novel White Jacket

- Abraham Lincoln’s public remarks on the Mexican-American War delivered in 1846

- Theodore Roosevelt resigning as Assistant Secretary of the Navy in 1898 to take a military command in Cuba

Lincoln remarked that President Polk had unnecessarily and unconstitutionally commenced a war with Mexico.

Thanks for watching, and happy studying!