Hello, and welcome to this discussion on domestic violence.

In this video, we will begin by reviewing various types of domestic violence. We’ll examine federal laws addressing this significant public health issue, and we will identify populations disproportionately affected. We’ll also cover risk factors, the cycle of violence, and treatment recommendations.

What is Domestic Violence?

Domestic violence, as defined by the National Coalition Against Domestic Violence (NCADV), is “the willful intimidation, physical assault, battery, sexual assault, and/or other abusive behavior as part of a systematic pattern of power and control perpetrated by one intimate partner against another. It includes physical violence, sexual violence, psychological violence, and emotional abuse. The frequency and severity of domestic violence can vary dramatically; however, the one constant component of domestic violence is one partner’s consistent efforts to maintain power and control over the other.”

Domestic Violence vs. IPV

Domestic violence and intimate partner violence, or IPV, are terms that are often used interchangeably; however, there are differences. IPV refers to abusive behavior by individuals in intimate relationships, including former or current spouses, partners, and other romantic relationships. Domestic violence is generally limited to individuals residing in the same household, including spouses, partners, children, step-children, extended family, non-romantic roommates, and siblings.

Interpersonal Violence

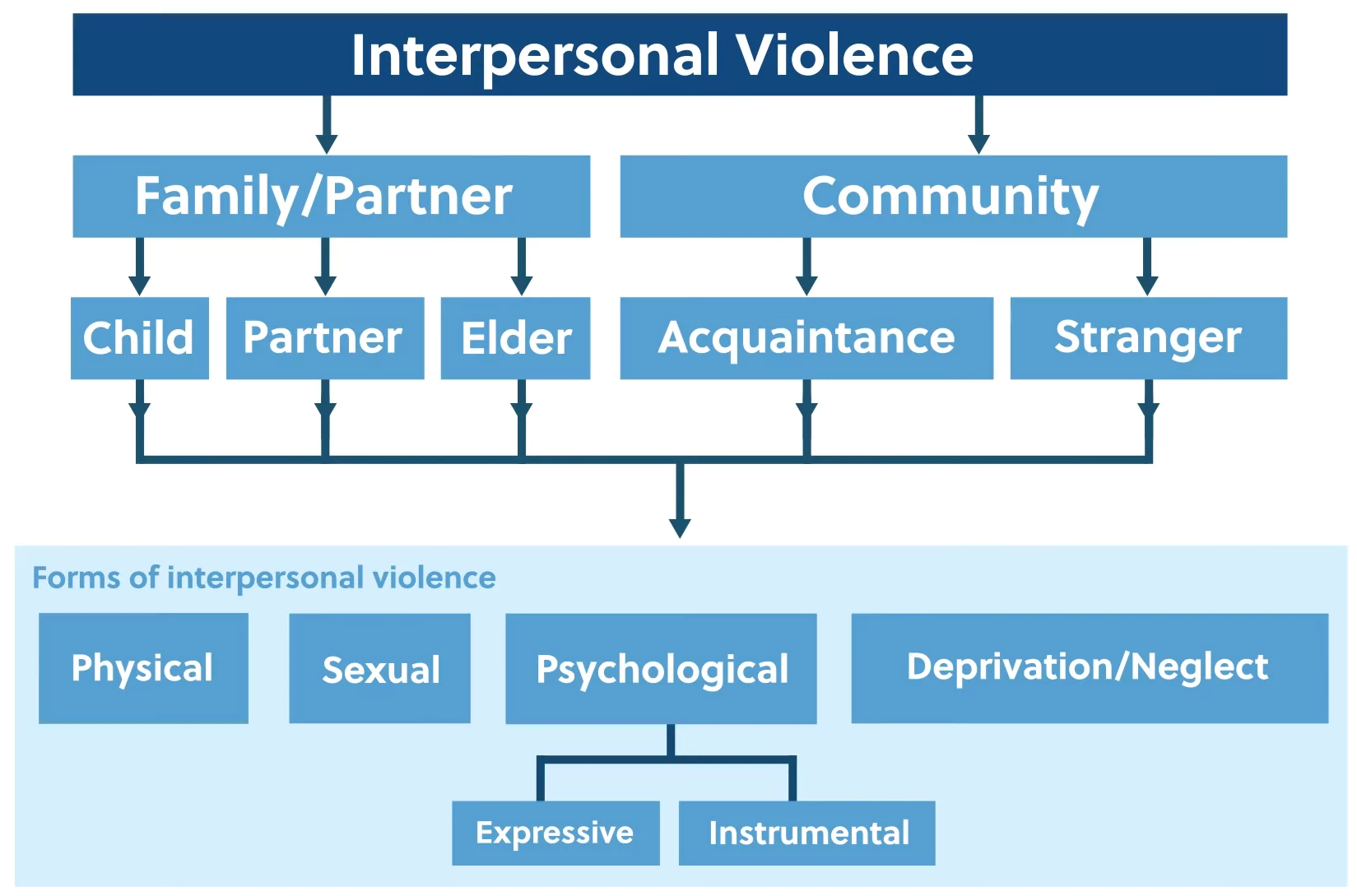

Interpersonal violence is an umbrella term for family or partner violence and community violence, with the latter referring to violence between strangers or acquaintances. While definitions vary, the common thread is one person exerting power and control over another. This graph is based on data provided by The Violence Prevention Alliance:

You’ll see that family or partner violence can occur with children, partners, or elders. The section at the bottom indicates different forms of interpersonal violence that can occur.

Physical Violence

Physical violence refers to actions intending to harm, injure, or cause death. Examples of physical violence include restraining, slapping, punching, biting, burning, striking with an object, strangulation, and the use of weapons.

Sexual Violence

Sexual violence includes attempted or completed sexual acts, including nonconsensual oral, vaginal, or anal sex, as well as genital touching. Partners experiencing sexual violence may be forced to engage in sexual behaviors with persons outside of the intimate relationship. Partners forced into nonconsensual sex may be minors, individuals under the influence of drugs or alcohol, or those unable to decline due to fear, intimidation, illness, or disability.

Psychological Violence

Psychological violence, the most common form of IPV, involves the deliberate use of words to intentionally harm, hurt, or incite fear in an intimate partner. Manipulation and intimidation are hallmarks of psychological violence. Because of its chronic and insidious nature, its impact can be long-lasting.

There are two subtypes of psychological violence: expressive and instrumental.

Expressive abuse includes verbal put-downs and behaviors that weaken a partner’s self-worth. This form of abuse is sometimes categorized as emotional abuse.

Instrumental Abuse

Instrumental abuse involves attempts to control the partner through threats, surveillance, economic abuse, use of children, and other coercive actions. As a way to exert control over the daily lives of their victims, abusive partners may intentionally isolate them from friends and family. Degradation, intentional embarrassment, and humiliation are common psychologically abusive tactics.

Psychological violence in LGBTQIA+ communities manifests in various ways. Persons in same-sex relationships may threaten to “out” their partner or publicly disclose sexual proclivities that go against societal norms. Members of the transgender community are especially vulnerable, with partners using slurs, “dead names,” or intentional misgendering as a means of hurting and weakening their partners.

Oftentimes, technology is used to facilitate psychological abuse. IPV incidents include online harassment and exploitation, showing explicit digital images without permission, stalking through surveillance, and nonconsensual searches of a partner’s email or social media accounts. Technological abuse also applies to mobile devices, location tracking, or other communication technologies.

Deprivation and Neglect

Deprivation and neglect include withholding medical care, food, or shelter. This form of abuse is most common among children and dependent adults. With deprivation and neglect, there is a complete disregard for the dependent person’s emotional or social needs. Failure to provide transportation, money, or access to friends and family may also occur, particularly among people with physical or developmental disabilities. Individuals age 65 and older are more prone to financial exploitation by their adult children or partners.

Community Violence

Interpersonal violence also includes community violence inflicted by strangers or acquaintances. While this is outside of the scope of this video, it is important to differentiate this form of violence from domestic and intimate partner violence.

Federal Laws

While state and local authorities handle most domestic violence cases, there are federal laws providing protection. The Violence Against Women Act of 1994, with additions made in 1996, was the first of its kind to recognize domestic violence as a federal crime. Under this law, victims reporting domestic violence are afforded several rights, including the right to privacy, restitution, and freedom from retaliation. Victims are also provided information on the conviction, sentencing, and release of the offending partner.

In 2022, the Violence Against Women Act was reauthorized to include additional violence prevention initiatives. Some of these initiatives include addressing cybercrimes, penalizing nonconsensual distribution of digital images, and broadening services to marginalized and culturally specific populations.

Effects of Domestic Violence

Effects on the Economy

Domestic violence costs the American economy a staggering $8.3 billion per year. Individuals who experience IPV miss a combined total of 8 million work days annually. Excessive absenteeism often leads to job loss and can be further complicated by prolonged illness, financial failure, depression, post-traumatic stress, substance use, and increased mortality.

Effects on Children

Children exposed to domestic violence are negatively impacted in nearly all areas of development. The effects on a child’s psychological, behavioral, social, and educational development can persist through adulthood.

Common complications for children and adolescents include:

- Depression

- Anxiety

- Aggression

- Poor self-esteem

- Deficient social skills

- Inadequate problem-solving skills

- Delinquency

- Oppositional behaviors

- Substance use

- Social withdrawal

- Truancy

- Cognitive impairment

- Physical illnesses

- Negative educational outcomes

Effects on Other Populations

While no one is immune to domestic or intimate partner violence, there are some populations that are disproportionately affected. For men and women, the highest prevalence occurs among non-Hispanic multiracial persons, followed by African Americans, Native Americans, and Alaska Natives.

Other populations disproportionately affected by IPV include:

- Individuals with disabilities

- Women

- Persons who are LGBTQIA+

- Youth between the ages of 18 and 25

- Persons with HIV

- Immigrant women

- Individuals with substance or alcohol use disorder

- People who are pregnant

- Individuals with low educational attainment

- Marginalized populations

It is estimated that 1 in 4 women and 1 in 7 men have experienced severe physical violence by an intimate partner. Individuals who commit domestic violence often have a history of witnessing domestic violence growing up or experiencing child abuse. Abusive partners are more likely to exhibit diagnostic symptoms of substance use disorder, externalized disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder, and antisocial personality disorder. Those belonging to cultural groups condoning violence or having norms perpetuating gender inequity are also at an increased risk. Other factors of abusive partners include interpersonal difficulties, unemployment, isolation, and financial instability.

Risk Factors

Identifying risk factors for individuals who perpetuate IPV is critical for increasing public awareness, making informed policy recommendations, and developing prevention and intervention strategies. While several factors contribute to IPV, victims’ advocates emphasize that committing violent acts is a choice with planned, purposeful, and progressive patterns.

Cycle of Abuse

In 1979, Lenore Walker described patterns of domestic violence that continue to be widely circulated to this day. Walker developed a cycle of violence consisting of the following phases:

Phase 2: Violent incidents. As tensions continue to rise, violent incidents occur as the family is placed in acute crisis or disequilibrium.

Phase 3: Contrition or remorse. In the aftermath of violence, the abusive partner may offer gifts and apologies. Promises are made ensuring incidents will not reoccur or that the offender has changed.

Phase 4: Calm. During the period of calm, the person inflicting violence makes excuses and may rationalize or minimize the abusive incident.

The intermittent periods of contrition and calm often keep victims from leaving the home. On average, it takes victims between 7 and 10 times before finally leaving for the last time.

Let’s take a look now at treatment for individuals experiencing IPV.

Treatment

It is recommended that clinicians screen at-risk individuals and those disproportionately affected by IPV, particularly women of reproductive age. Widely-used screening tools include HITS, HARK, and PVS.

Clinicians screening for IPV are encouraged to develop a script to promote engagement and trust. A script might start with a framing statement like, “I’m going to ask you a couple of questions about IPV. I ask these questions to all of my clients.” During the screening, a normalizing statement may also be included in the script. For example, “We know that all couples fight. When you fight with your spouse, does it involve hitting, yelling, etc.?” If a person screens positive, clinicians thank them for sharing and provide empowering statements, such as, “I believe you. No one deserves to be treated like this. Help is available.”

It is crucial that individuals with positive screenings feel supported and safe. Working with people impacted by domestic violence must include a trauma-informed care approach, couched in the principles of autonomy, empowerment, safety, awareness, and inclusivity.

Clinicians are discouraged from immediately discussing actionable steps to end the abuse. Instead, it is recommended that providers first acknowledge the trauma, assess immediate safety, and ask the person if they are open to receiving help. This is followed by discussing various options and encouraging safety planning. Individuals are at heightened risk if the offender has recently been released from jail or violated a protective order. Best practices for safety plans are that they are brief, easy to follow, collaborative, and reviewed frequently.

Treatment for the abusive partner must first include attempts to identify and treat any co-occurring mental or substance use disorders. Treatment is rarely pursued by the offender, with court-mandated treatment being the most common. Mandated domestic violence programs, or batterer intervention programs, are aimed at rehabilitation and ordered for individuals who have been criminally charged with physical or sexual assault, manslaughter, aggravated stalking, false imprisonment, psychological manipulation, and emotional abuse.

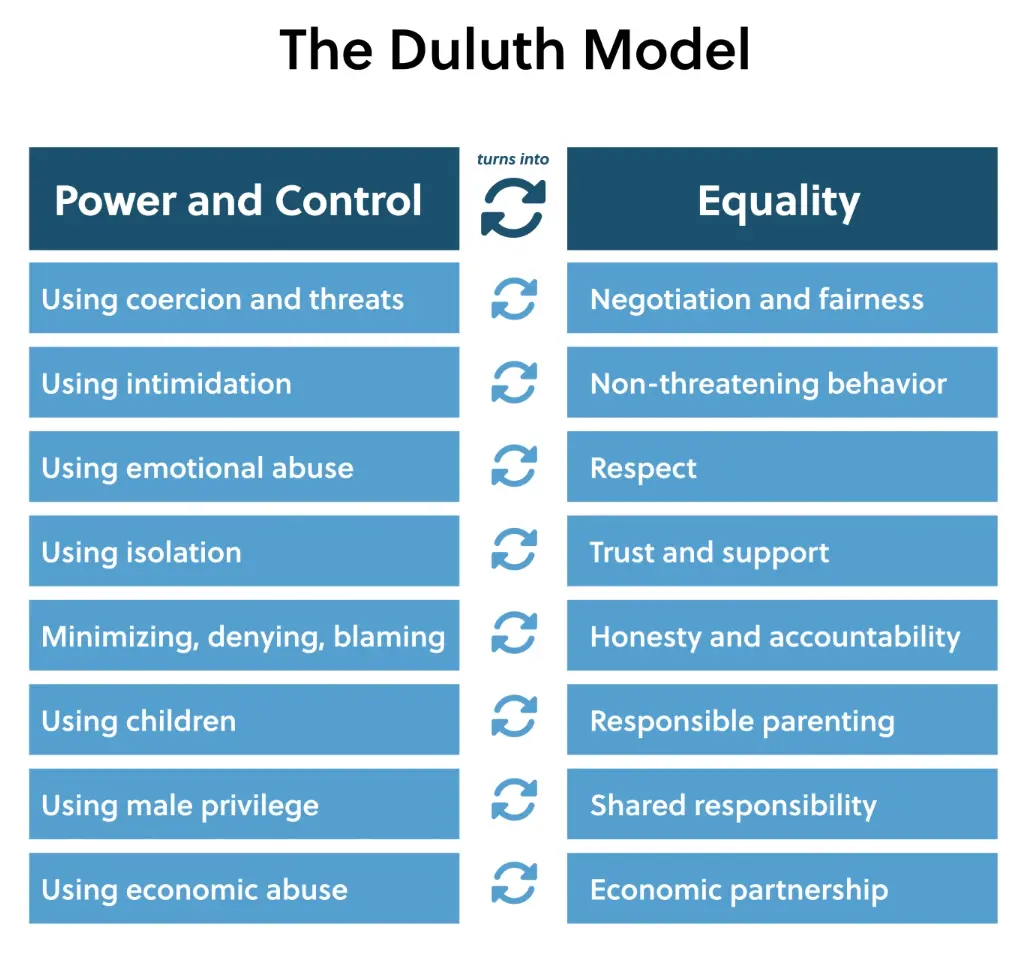

The Duluth Model

Most batterer intervention programs use the Duluth Model, which focuses on treating men who are criminally charged with domestic violence. The main goal of the Duluth Model is to dismantle patriarchal systems of power used to perpetuate violence against women. This is accomplished by coordinating community responses with victims, advocacy groups, local police, domestic violence shelters, and criminal and civil justice programs. Participants attend psychoeducational groups where they learn patterns of abusive behavior and develop skills to reduce violent recurrences through establishing gender egalitarian behaviors.

The RNR Model

The risk-need-responsivity (RNR) model is also aimed at reducing recidivism rates for domestic violence offenders. This model is based on three principles:

- The risk principle assumes that the probability of criminal behavior can be reasonably predicted.

- The need principle emphasizes criminogenic needs or factors that perpetuate IPV.

- The responsivity principle focuses on circumstances contributing to treatment adherence.

Interventions are then tailored based on individualized needs, motivations, abilities, and risks.

Alright, that’s all the information we’re going to cover in this video. I hope it’s been helpful.

Thanks for watching, and happy studying.