Hi, and welcome to this video about heart failure.

Anatomy of the Heart

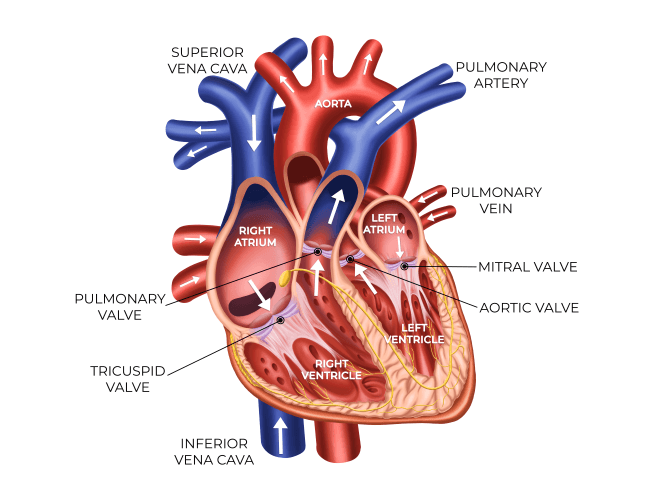

First, let’s take a minute to review the anatomy of the heart.

The superior vena cava brings blood into the right atrium, and when the atria contract, the blood flows through the tricuspid valve into the right ventricle.

When the ventricles contract, the blood flows from the right ventricle through the pulmonary valve and into the pulmonary artery to the lungs.

Once oxygenated, the blood returns to the left atrium through the pulmonary veins and then through the mitral valve into the left ventricle. From here, the blood goes through the aortic valve and into the aorta and general circulation.

When the atria contract, the ventricles fill; and when the ventricles contract, blood leaves the heart and the atria fill.

Thus, with a healthy cardiovascular and respiratory system, the heart is continually pumping and the blood is circulating without damage to the heart. However, if something impairs this flow of blood, such as hypertension and plaque buildup, the heart can become damaged, resulting in heart failure.

Types of Heart Failure

The American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association classification system for heart failure considers structural disorders and symptoms.

- Class A indicates high risk for heart failure because of conditions that are associated with heart failure, such as diabetes, but the person does not have identified structural or functional abnormalities and no signs or symptoms of heart failure.

- Class B indicates that structural heart disease strongly associated with heart failure is present, but the person has no signs or symptoms.

- Class C indicates that there are current or prior symptoms of heart failure associated with underlying structural heart disease.

- Class D indicates that advanced structural heart disease and marked symptoms of heart failure are present at rest despite medical interventions.

Heart failure can be classified according to the type of impairment (systolic or diastolic) or the area of impairment (left or right ventricle). Typically, heart failure begins as left ventricular/systolic failure and progresses to right ventricular failure.

- Systolic failure refers to the inability of the ventricles to pump adequately. With this type of failure, the ejection fraction falls. The ejection fraction is the percentage of blood that is pumped from ventricles with each contraction (primarily referring to the left ventricle). This should range from 55% to 75% but may fall below 40% with systolic failure.

- Diastolic failure refers to the inability of the ventricles to fill adequately, so the cardiac output drops while backpressure increases in the respiratory and vascular systems. With diastolic failure, the ejection fraction typically remains within normal limits, but pulmonary hypertension is present.

- In some cases, mixed systolic/diastolic failure may occur, resulting in pulmonary hypertension but with a decreased ejection fraction.

Left Ventricular Failure

Left ventricular failure is the type of heart failure commonly associated with hypertension, which causes the left ventricle to work harder to overcome systemic vascular resistance, resulting in increased need for oxygen and left ventricular hypoxia. This impairs the ability of the muscle to contract, so cardiac output decreases. The left ventricle begins to dilate, hypertrophy develops, and pulmonary pressure increases as blood backs up into the left atrium and pulmonary veins, resulting in pulmonary edema.

Complications of left ventricular failure include:

- Signs of pulmonary edema, including dyspnea on exertion, orthopnea, and paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea

- Cough, usually dry and hacking initially but progressing to moist and productive with blood-tinged sputum

- Decreasing oxygen saturation below 95%, and cyanosis

- Gallop rhythms, including S3 and S4 heart sounds

- Respiratory changes, including crackles, rales, wheezes, and pleural effusion

- Renal changes, such as oliguria related to impaired perfusion and nocturia

- Digestive disturbances, such as nausea and vomiting, because of impaired perfusion of the gastrointestinal tract

- CNS disorders associated with decreased perfusion, including confusion, dizziness, and anxiety

- Tachycardia as the heart works harder to compensate

- Cool, clammy skin from constriction of the peripheral vascular system to increase perfusion of internal organs

- Generalized fatigue

Right Ventricular Failure

Right ventricular failure is almost always a progression from left ventricular failure, so the symptoms of right ventricular failure are usually superimposed on those of the left.

With right ventricular failure, the right ventricle is unable to adequately pump blood through the pulmonary artery to the lungs, so the right ventricle dilates and fluid begins to back up in the tissues, resulting in central and peripheral edema.

Complications of right ventricular failure are those that are commonly associated with heart failure and include:

- Jugular venous distention from increased venous pressure.

- Edema including peripheral edema, ascites, sacral edema for those on bedrest, and anasarca, or severe generalized edema.

- Hepatosplenomegaly. AND

- Weakness resulting from decreased cardiac output, inadequate circulation, and buildup of waste products.

The body attempts to compensate for heart failure by doing the following:

- The chambers of the heart dilate, the heart enlarges, and the heart muscle becomes less elastic.

- The walls of the chambers begin to undergo hypertrophy and stiffen.

- The sympathetic nervous system activates with release of increased epinephrine and norepinephrine, resulting in tachycardia and peripheral vascular constriction, which increases venous return to an already congested heart.

- Sodium retention and vasoconstriction develop to improve renal perfusion.

- Decreased cerebral perfusion causes the pituitary gland to release increased antidiuretic hormone to increase water reabsorption in order to increase blood volume and cardiac output.

- Eventually, ventricular remodeling occurs with the ventricles enlarging and walls thinning to increase cardiac output, but ventricles become weaker and less effective.

What Causes Heart Failure?

- Coronary artery disease is implicated in 60% of cases of heart failure. As circulation is impaired in the coronary arteries, the heart muscle does not receive adequate oxygenation, and this interferes with both the conduction system and ventricular contractile ability.

- Cardiomyopathy is another cause of heart failure. The heart muscle weakens and cannot adequately pump blood.

- Hypertension, often associated with plaque formation, increases systemic vascular resistance, so the heart has to work harder to pump blood.

- Valvular disease, such as stenosis, can cause hypertrophy as the heart has to work harder to overcome the restriction. Valvular regurgitation can cause dilation of the ventricles and impaired ability to contract.

- Some arrhythmias require the heart to work harder to effectively circulate blood.

- Obesity also requires the heart to work harder.

- Diabetes mellitus is often associated with hyperlipidemia and hypertension, and hyperglycemia by itself can damage the heart muscle.

- Infections, such as endocarditis, may damage the heart.

- Kidney disease can lead to sodium retention and hypertension, both causing the heart to work harder.

- Some may have a genetic predisposition or congenital heart defects. AND

- Unhealthy lifestyle choices including smoking, lack of exercise, excessive alcohol intake, and diets high in sodium, sugar, and saturated fats can damage the heart.

Treatments

The first step to treatment of heart failure is identifying and treating the underlying cause, so treatment approaches may vary, but common treatments include:

- Lifestyle changes, such as increased rest, an exercise program, weight reduction, and diet. A common diet is the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension, known as the DASH diet. This is a diet that is low in sodium and saturated fats and encourages whole grains, fruits, and vegetables.

- Smoking cessation is an important factor because smoking increases the risk of coronary artery disease and impairs oxygenation.

- Oxygen may be necessary if pulmonary edema is severe.

Some people may require an implantable cardioverter defibrillator or biventricular pacing, especially those with ejection fractions of less than 35%.

Medications

Medications are commonly used to control symptoms of heart failure and include:

- Diuretics, which are used to reduce edema. These include thiazides, such as hydrochlorothiazide; loop diuretics, such as furosemide, or potassium-sparing diuretics, such as spironolactone, which are often used along with other diuretics to reduce the risk of hypokalemia.

- ACE inhibitors, such as captopril along with a diuretic are often a first-line treatment for heart failure. ACE inhibitors have vasodilation properties.

- Angiotensin II receptor blockers or ARBs may be added to ACE inhibitors or used in place of them if a person cannot tolerate the ACE inhibitor.

- Beta-blockers, such as carvedilol or metoprolol, help block the effects of the sympathetic nervous system and may be administered along with ACE inhibitors, diuretics, and digitalis.

- Digitalis glycosides, such as digoxin, are used infrequently, but may be indicated for atrial fibrillation.

- Calcium channel blockers, such as amlodipine, may be used for diastolic dysfunction but may worsen heart failure, so they are usually avoided.

According to the American Heart Association, over 300,000 deaths are caused by heart failure and about 960,000 new cases are diagnosed every year in the United States. For almost all patients, heart failure is a chronic condition that must be continually managed, so preventive measures, including healthy lifestyle choices, are essential.

That’s all for this review! Thanks for watching, and happy studying!