Through four monumental voyages in the late-15th and early-16th centuries, explorer Christopher Columbus discovered the continents that would become known as the Americas. In so doing, he launched an enormous exchange of cultures in the New World that would result in the founding of the Spanish Empire and eventually settlements by other European powers. But he was a complex man, and his discoveries were made possible by a combination of technology, geopolitics, religion, and capitalism.

Early Life of Columbus

Born in Genoa in 1451, Columbus ventured to sea starting at an early age. While in his teens, he worked on a merchant ship and was actually attacked by pirates off the coast of Portugal in 1476. Though the ship sank, Columbus hung onto a piece of driftwood and floated to shore, eventually moving to Lisbon where he studied mathematics, astronomy, cartography, and navigation.

Inspiration for Navigation

Columbus was captivated by the intellectual fervor initiated by Portugal’s Prince Henry the Navigator, who had innovated the swift, ocean-worthy caravel ship and set the Portuguese sights on finding new sea routes to access the profitable trade of “India,” which then was a term that Europeans used to refer to all of South and East Asia. The Portuguese thought such gains would best be gotten by rounding the southern coast of Africa and heading east, and by 1488, they had reached the Indian Ocean. Columbus disagreed with this approach, believing that a faster, more direct route to the riches of Asia existed across the Atlantic Ocean to the west. It was this scheme that he began hatching to differentiate himself and thereby claim his place among the era’s great explorers.

Northwest Passage

Steadfast Portuguese interests were against him though, since Lisbon already had a string of trading depots along the African coast. Rejected by Portuguese rulers, Columbus made his case for what he termed a “Northwest Passage” to rulers in Spain and England. Eventually, he received support from the newly minted monarchs King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella of Spain—Portugal’s main rival for an overseas empire. Having signed a contract in which he was promised 10 percent of whatever riches he discovered, along with the noble title “admiral of the ocean seas” and governorship of any lands found, Columbus embarked with a crew of 87 men from Palos, Spain on August 3rd, 1492 on three ships: the Niña, the Pinta, and the Santa Maria.

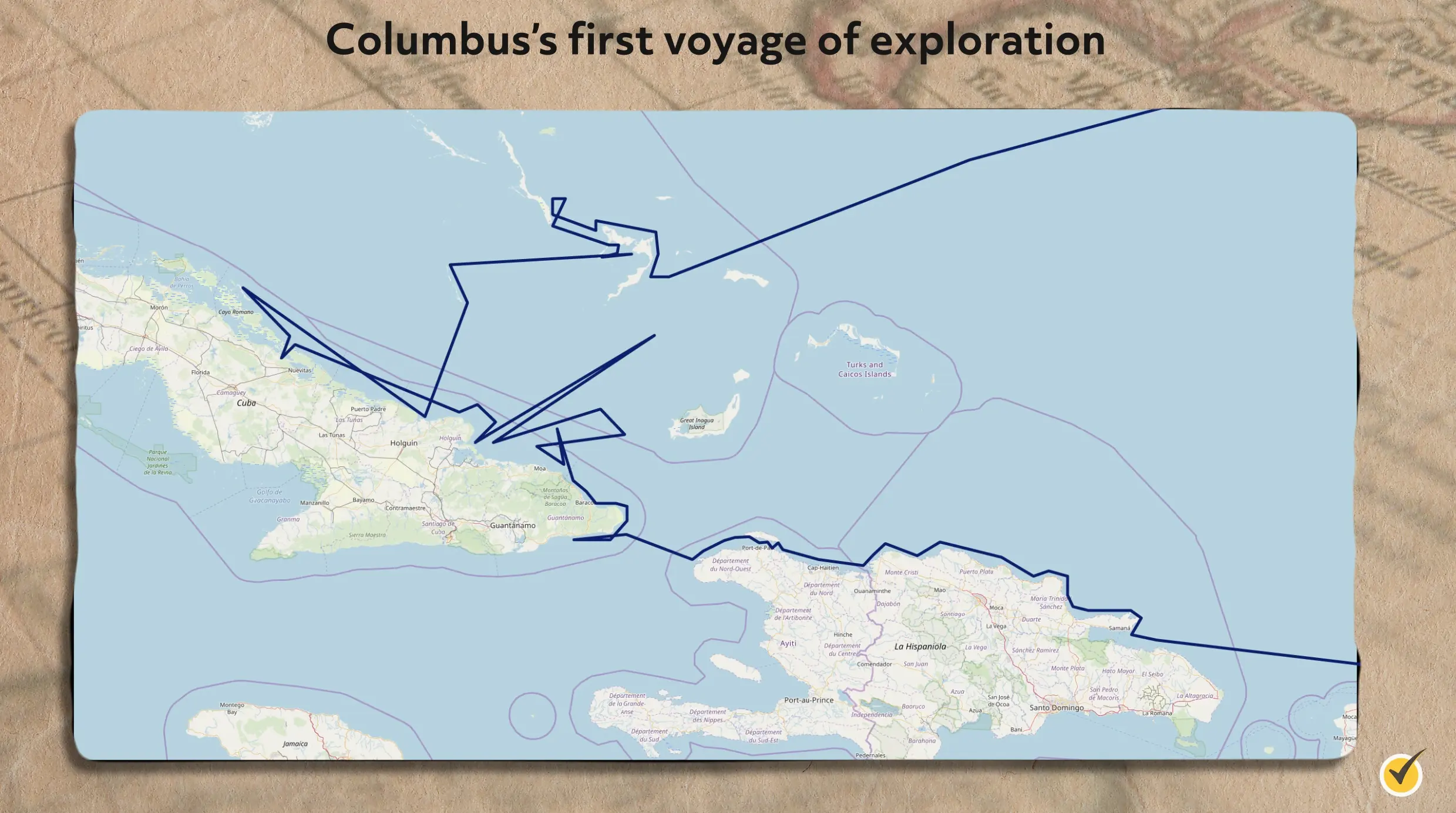

First Voyage

Utilizing the dry magnetic compass, the Portuguese caravel ship design, and Portuguese-discovered trade winds in the Atlantic – all key navigational innovations of the age – Columbus’s ships were able to travel at a fast clip, covering roughly 150 miles per day. Touching land first in the Canary Islands, he sailed west and eventually landed on a Bahamian island, probably San Salvador, on October 12th. Exploring the Bahamas and continuing on to Cuba and Hispaniola (the island containing modern-day Haiti and the Dominican Republic), he scoured these newly discovered islands for the precious metals he had set out to find, to enrich himself and the Spanish crown. Though findings in that area were minimal, he was able to scrape together enough gold to entice his backers in Spain. When he set sail for Europe in January 1493, he left a group of settlers on the island of Hispaniola in a colony named “La Navidad.”

In the journal of his first voyage, he assessed the native people he had come into contact with as prime candidates for servitude. This high-handedness has earned Columbus criticism, but supporting colonial expansion was the name of the game for explorers in late 15th-century Europe.

Second Voyage

Deploying his assessments and his newfound stash of gold effectively, Columbus duly received backing for a return voyage, on a grander scale than that of the first. With 17 ships, more than 1,000 paid staff, roughly 200 private investors, and several friars under his charge, he left Cádiz in September 1493 at the head of a Spanish colonizing mission. Yet when he returned to the Americas, he found La Navidad, the one colony he had already established, in ruins, along with 11 Spanish corpses – the work of the Taino people. Forced into war, Columbus began conscripting hundreds of indigenous people into slavery and tasking his brothers Bartholomew and Diego with rebuilding the Spanish presence on Hispaniola. He continued searching for mother lodes of precious metals, but didn’t find them. So, by way of intended compensation, he enslaved 500 natives and sent them to Queen Isabella. She flatly refused the gift, asserting that peoples discovered by Columbus were Spanish subjects who could not be enslaved.

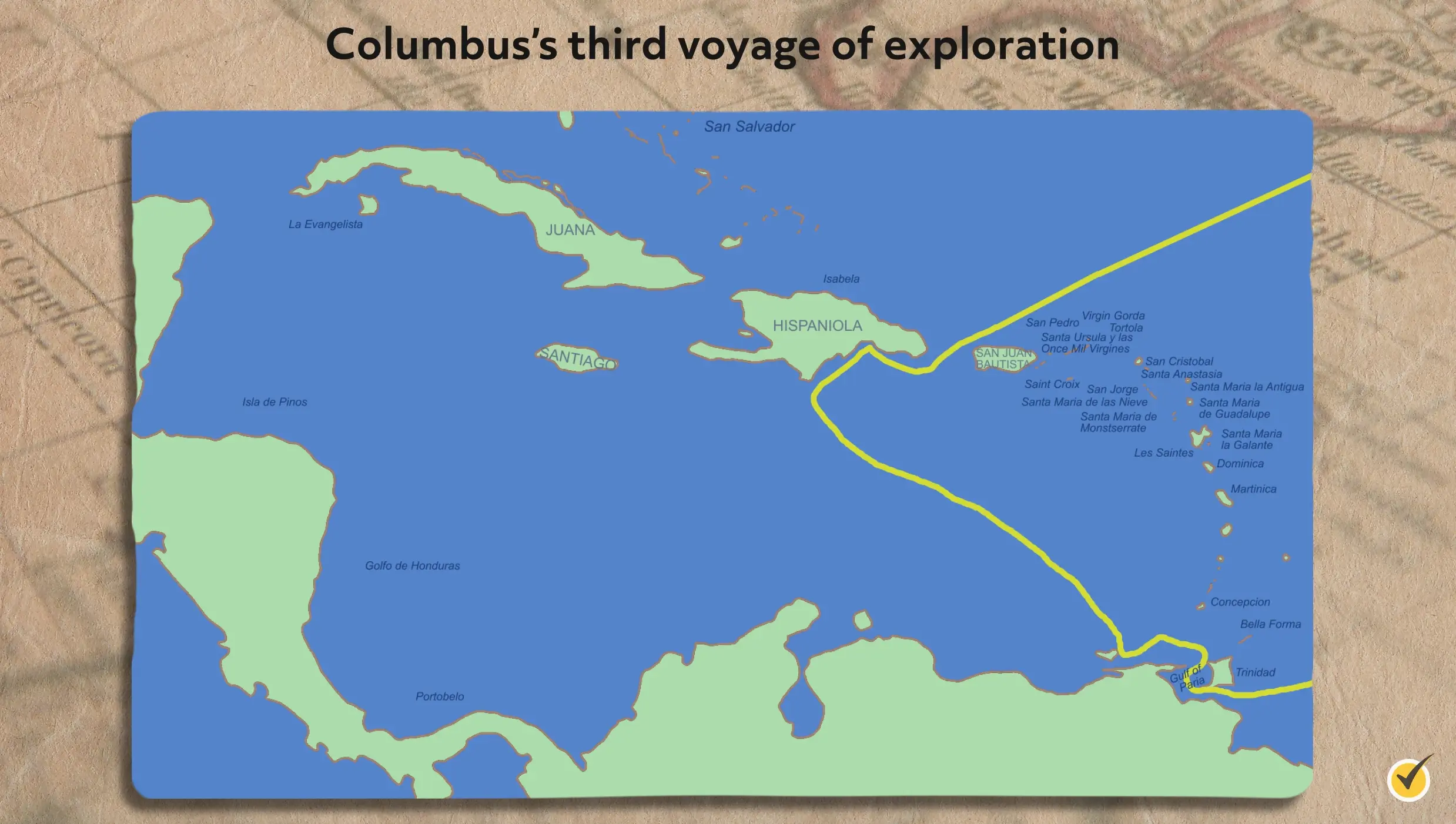

Third Voyage

On his third voyage in 1498, Columbus veered south, still looking for India but instead finding Grenada, Margarita, and Trinidad and Tobago. His obsession with unearthing gold had by this time become notorious, and as a result the Columbus family got out of control in their governance of American territories. Bartholomew and Diego ruled Hispaniola with violent impunity and eventually had to be replaced. During his term as “Viceroy and Governor of the Indies,” Columbus sanctioned massive enslavement of the Taino to further his fanatical quest for gold, and the resulting overwork severely reduced the population of that indigenous people. He regularly sanctioned chopping off the hands of natives who couldn’t find enough gold and didn’t shirk from executing rebellious Spaniards. Madrid eventually got word of complaints from colonists, and a royal commissioner had Columbus arrested in August 1500 and sent to Spain, in shackles, to argue his case before Ferdinand and Isabella.

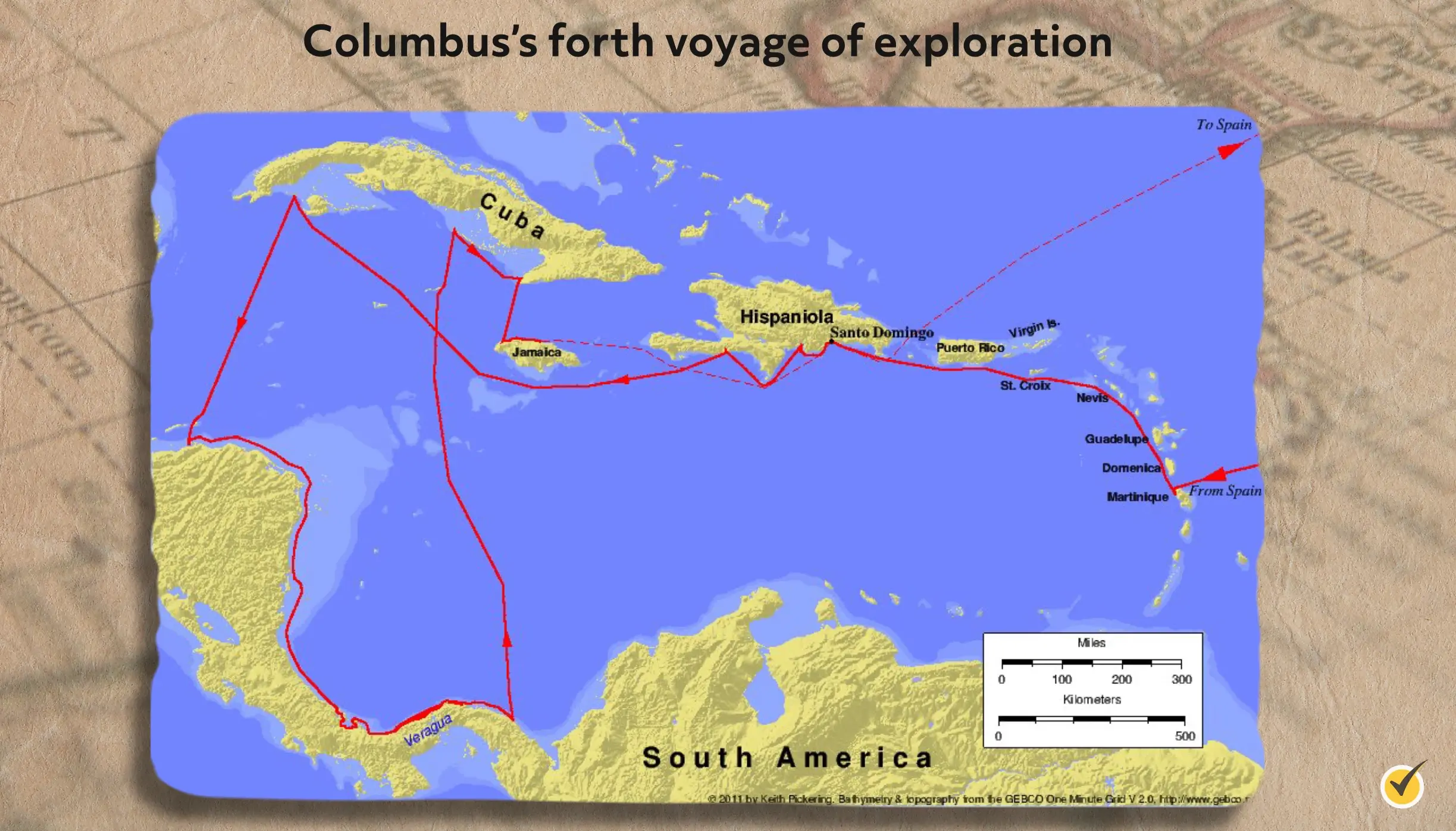

Fourth Voyage

Though Columbus was a tyrannical governor, his skills as an explorer were unquestionable. This is thought to be the simple reason which probably led the Spanish monarchs to acquit him and equip him for a fourth voyage, which left in 1502. Still tasked with trying to find India, Columbus explored the eastern coast of Central America, encountered several storms, and was stranded on Jamaica until being rescued by an expedition from Hispaniola, eventually returning to Spain in 1504.

Death and Legacy of Columbus

Believing throughout that he had discovered unknown lands in the Far East, Columbus died without receiving wealth due to him and stripped of his noble titles. He wasn’t the first European to land in the Americas – that honor belongs to Leif Eriksson, a Viking explorer who explored the eastern coast of modern-day Canada around the year 1000. But Columbus’s discoveries marked the beginning of large-scale European emigration to and colonization of American lands.

Because of his navigational skills, vivid imagination, rhetorical skills, and even perhaps his fervent religious faith that embraced both Christianity and Judaism, he re-discovered the Americas, thereby sparking transatlantic trade between Europeans and Americans that was – and is – one of the largest trading relationships in the world. Thanks to Columbus’s discoveries, Europeans would be introduced to cocoa, vanilla, maize, potatoes, sweet potatoes, and tobacco from the Americas. Though Christopher Columbus was a somewhat unpredictable individual with positive and negative qualities, his daring feats of exploration undoubtedly changed the course of history.

Review

Before we go, let’s look at a review question:

During Christopher Columbus’s first voyage of exploration in 1492-93, he

- Became the first European since Leif Eriksson to “discover” lands in what would eventually become known as the Americas.

- Sailed using the dry magnetic compass, caravel ships, and the trade winds of the Atlantic, allowing his ships to cover roughly 150 miles per day.

- Mined gold near modern-day Havana, which he used as a down payment to fund his second voyage of exploration.

- Established a Spanish colony called “La Navidad” on the island of Hispaniola.

Thanks for watching, and happy studying!

- “Ocean Motion : Timeline : 1500 A.D.” n.d. Oceanmotion.org

- “Christopher Columbus: The Good, the Bad and the Ugly.” 2010. Americanthinker.com

- History.com Editors. 2009. “Christopher Columbus.” HISTORY. A&E Television Networks

- Klein, Christopher. 2018. “The Viking Explorer Who Beat Columbus to America.” HISTORY

- “Why Was Christopher Columbus Arrested in 1500? – Reference.com.” Reference

- Valerie I.J. Flint. 2019. “Christopher Columbus – the First Voyage.” In Encyclopædia Britannica

- Flint, Valerie. 2019. “Christopher Columbus – the Second and Third Voyages.” In Encyclopædia Britannica

- “What Christopher Columbus Discovered on His First New World Voyage.” ThoughtCo. 2019

- “Christopher Columbus.” 2023. Wikipedia

- Klein, Christopher. 2018. “10 Things You May Not Know about Christopher Columbus.” HISTORY

- “Voyages of Christopher Columbus.” 2022. Wikipedia

- The Mariners’ Museum and Park. 2017. “Christopher Columbus – Ages of Exploration.” Marinersmuseum.org

- “Columbian Exchange.” 2020. Wikipedia