Hi, and welcome to this video on arterial punctures! In this video, we will be looking at the overall process and the dos and don’ts when it comes to arterial punctures.

Let’s get started!

Sampling, Monitoring, and Interventions

To begin, let’s review what an arterial puncture actually is. An arterial puncture (usually called a radial artery puncture) is a procedure performed by accessing the arterial system by direct penetration of a peripheral artery, with a needle or catheter. This invasive procedure is performed in a variety of settings including hospitals, emergency rooms, ambulatory surgical centers, as well as vascular and interventional radiology centers.

There are a few different reasons that this procedure may be performed.

Obtaining Arterial Blood Samples

The first reason would be to obtain arterial blood samples, typically for arterial blood gas analysis. Also referred to as an arterial stick, this is a routine procedure in the care of many emergency department patients, and an essential component in the management of critically ill patients and patients undergoing either cardiac or respiratory surgery.

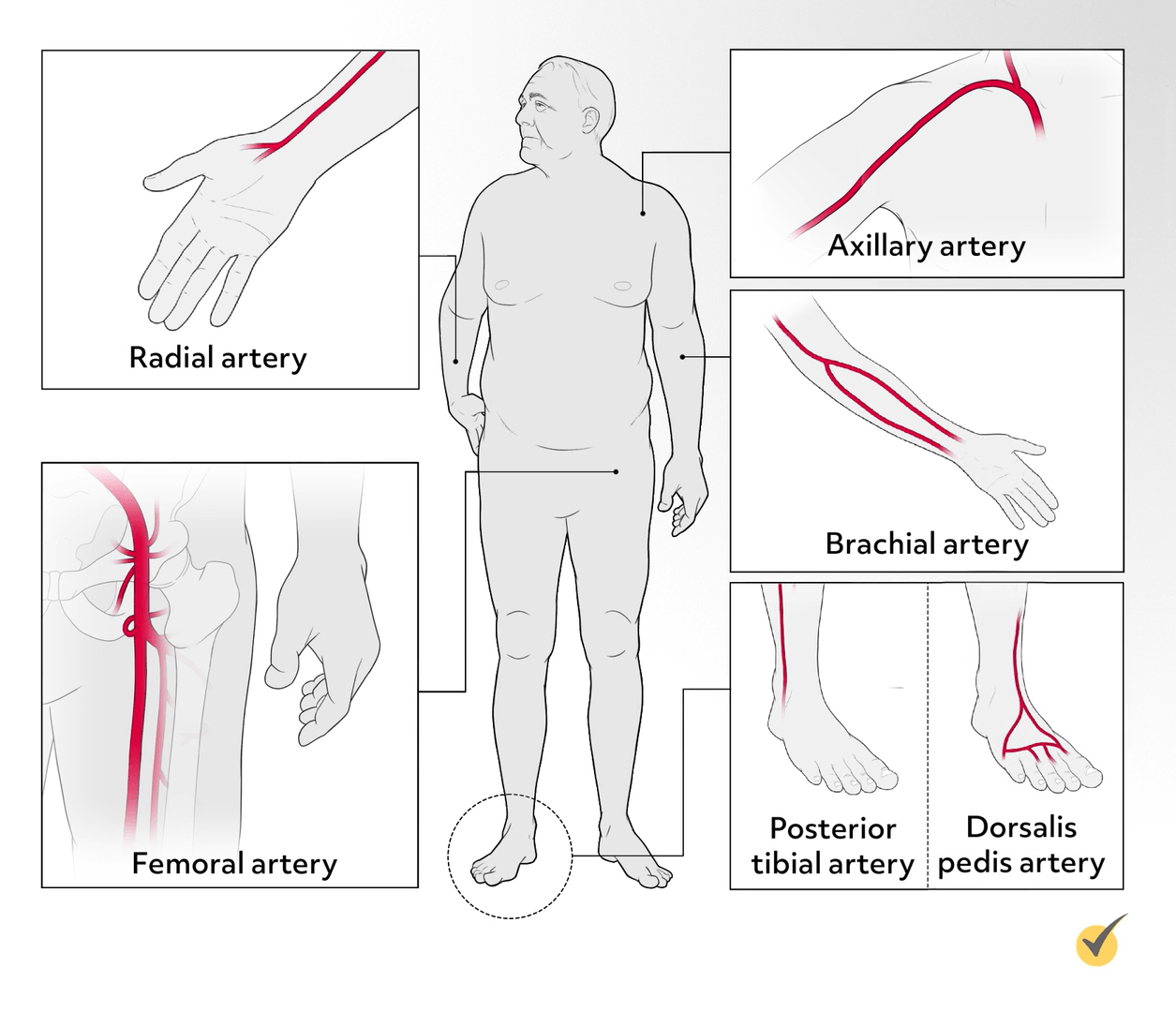

Several sites can be used for arterial blood sampling in both pediatric and adult patients, however, the radial artery is the preferred site. Alternative sites include the brachial artery, the dorsalis pedis artery, and the femoral artery, with the posterior tibial artery being a less-used option. In newborns, the umbilical artery can be used.

Placing an Arterial Line

The second reason for an arterial puncture would be for the placement of an arterial line. An arterial line is placed for patients who require continuous hemodynamic monitoring or monitoring of intra-arterial blood pressure (IAP) and titration of vasoactive medications.

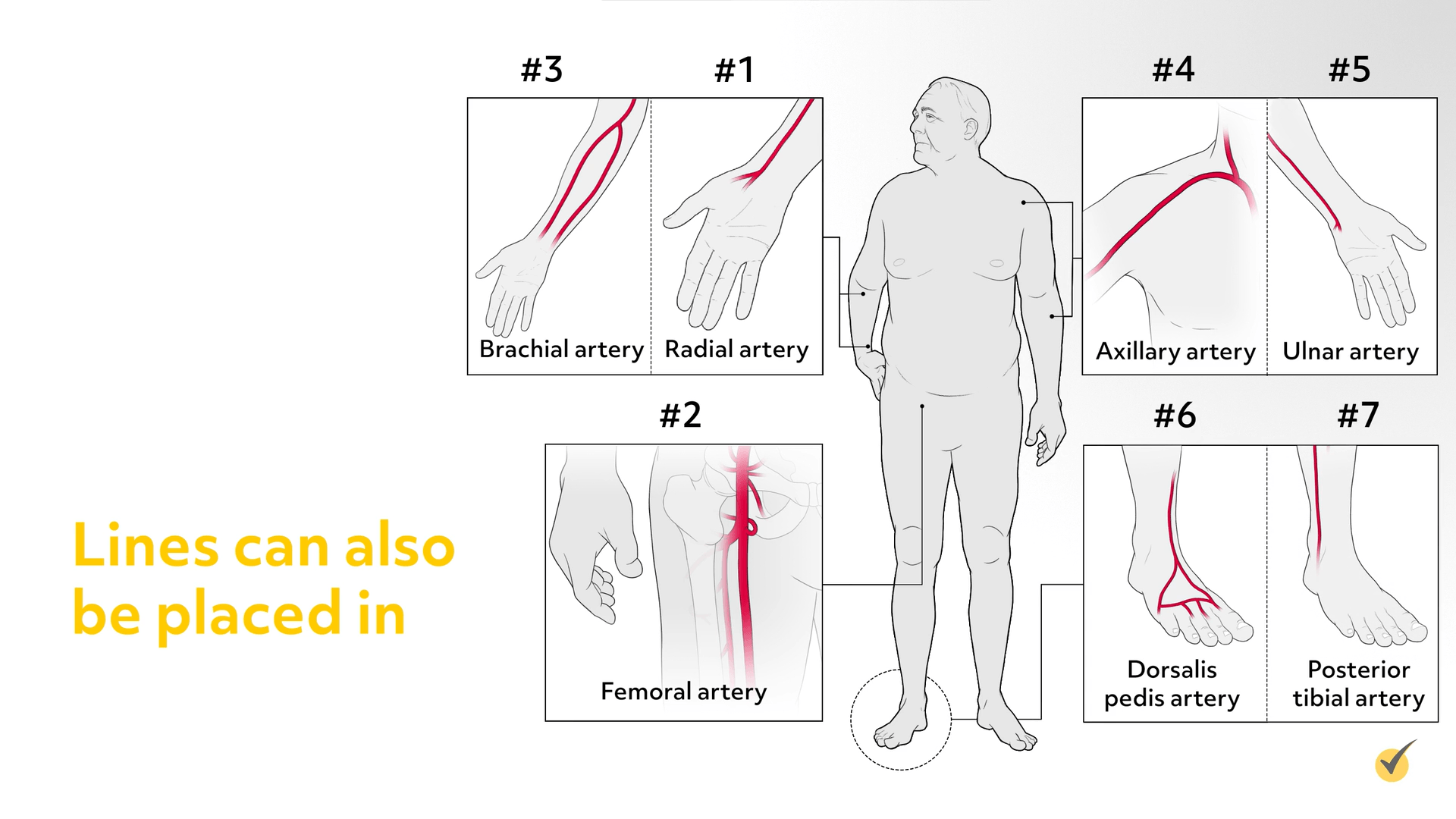

The predominately used sites for arterial line placement, in order of preference, are the radial, femoral, and brachial arteries, though lines can also be placed in the axillary, ulnar, dorsalis pedis, and posterior tibial arteries.

Providing Arterial Access Route

The third reason this procedure might take place is to provide an arterial access route for percutaneous or minimally invasive diagnostic procedures, such as cardiac electrophysiology study, percutaneous transluminal coronary arteriography, and endovascular interventions, such as percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).

Endovascular procedures are used to treat vascular disease and other conditions involving blood vessels, by threading a catheter through a percutaneous needle puncture into a blood vessel.

Site Selection and Complications

The femoral artery is the most common access site for percutaneous diagnostic or interventional procedures; however, due to the reduced risk of complications, radial access is increasingly being used, with alternative sites including the brachial, axillary, posterior tibial, and pedal arteries.

Minimizing Risk

Site selection for arterial puncture is extremely important and should be determined in advance. To minimize risk and ensure optimal patient outcomes, many or all of the following factors are taken into consideration when choosing the optimal site:

- Purpose for the puncture

- Proximity of the artery to the skin surface and surrounding structures

- Ability to locate the artery

- Ease of access

- Size of the artery

- Patient’s age and clinical status, including comorbid conditions such as thrombocytopenia, obesity, peripheral arterial vascular disease, use of anticoagulation medications

- Patient’s vascular anatomy, adequacy of collateral circulation, presence of an A-V graft, shunt or fistula

- Presence of lesions, scar tissue, inflammation or infection at a site

- History of recent punctures, previous peripheral vascular surgery

- Proximity of arterial access site to site of intervention

- Catheter/equipment dimensions

- Preference and experience of the clinician or phlebotomist

- Patient’s preference and hand dominance

Complications

Additionally, location of the puncture has implications for post procedural hemostasis, arterial closure, and vascular site complications. While considered safe, arterial punctures are not risk-free, and several factors are associated with complications, including:

- Number of attempts (successful rate of first-attempt puncture)

- Catheter dimensions/needle size

- Use of anticoagulant and antiplatelet agents

- Experience of the practitioner

Each site is associated with a set of major and minor complications, which can occur during or after the procedure. In general, potential complications include:

- Artery vasospasms;

- Arterial injury, dissection, extravasation, pseudoaneurysm, arteriovenous fistula

- Access/non-access site bleeding, ecchymosis and hematoma

- Ischemia, caused by arterial thrombosis, embolism, or occlusion

- Trauma or damage to adjacent structures (nerves, bones)

- Infection

At a minimum, when one of the following is required, the complication is classified as major:

- Treatment for ischemia

- Blood transfusion

- Vascular repair

- Surgical repair of nerve injury

- Antibiotic administration

To avoid potential devastating sequela, major complications require early recognition, prompt diagnosis and appropriate treatment.

Minimizing Complications

Now, let’s go over the ways that complications can be minimized.

- Adequate pre-procedural patient assessment.

- Selecting the most optimal puncture site with the lowest risk for complications.

- Appropriate patient positioning with the goal of providing optimal access to, and visualization of, the puncture site. Appropriate positioning techniques are associated with a significant increase in the success rate of arterial puncture. It is important to ensure that the patient’s limb is well-supported and immobilized.

- Adherence to aseptic technique, including antiseptic skin prep, to prevent the transmission of pathogenic microorganisms from the healthcare worker, equipment or the environment to the patient

Proper Puncture/Insertion Technique

Equipment and supplies used to puncture the artery are based upon the purpose of the procedure, and can vary between facilities. All equipment and supplies should be used in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. Needle or catheter size is based on procedure type, puncture site, patient size and age, however, the clinician should always use the smallest needle or catheter practical.

Based on the approach, the patient is positioned and the clinician, either by the landmark method or ultrasound, locates the artery. By gentle palpation, the clinician identifies the course and direction of the vessel and the ideal puncture site. The chosen site can be marked with a surgical ink pen. Ultrasound, Near-Infrared (nIR) light technology, or fluoroscopic guidance aids vascular visualization and improves puncture site accuracy.

Before selecting a radial approach, the adequacy of collateral circulation should be determined. The Modified Allen test is traditionally used for this purpose, however, Barbeau’s test (using pulse oximetry and plethysmography) or Doppler ultrasonography are more accurate methods of assessing collateral circulation.

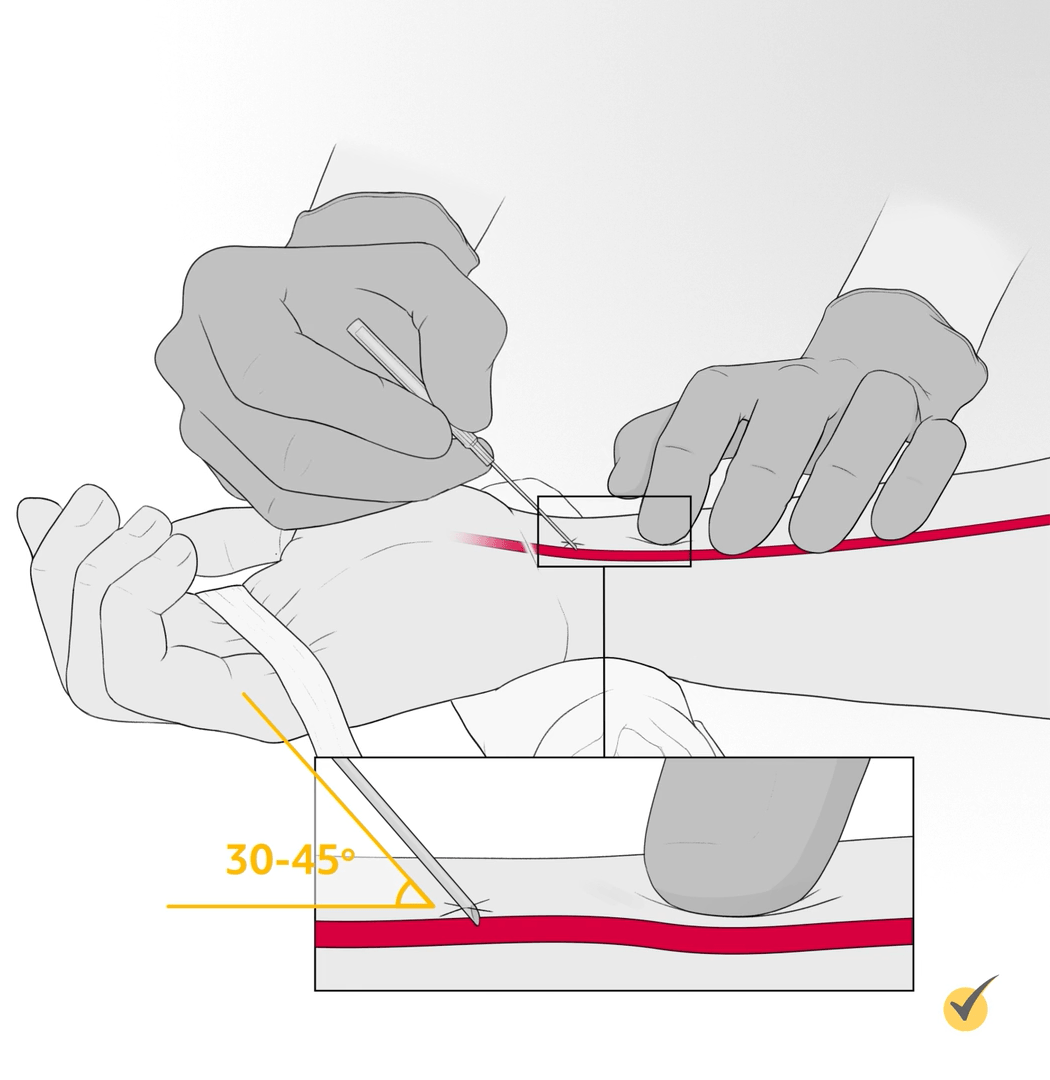

The clinician, using their nondominant hand, places a finger at the point where the needle should puncture the artery, approximately 5-10 mm proximal to the selected skin entry site. With the bevel of the needle up, the clinician holds the access device in their dominant hand as if it were a pencil and punctures the skin directly over the artery. The needle is advanced slowly toward the artery at a 30- to 45-degree angle until a flash of blood is seen in the hub. The needle is advanced a few millimeters further to ensure the entire bevel is in the lumen of the artery.

Adequate Post-Procedure Hemostasis and Monitoring

Achieving hemostasis can be affected by several factors, including

- The size of needle/catheter

- Length of time in place

- The patient’s blood pressure

- Current use of anticoagulant/antiplatelet medication

- Pre-existing coagulation disorders

After the procedure, the clinician (not the patient) should apply firm finger pressure at the puncture site until hemostasis is achieved (bearing in mind that the arterial puncture site and the needle entry points are not the same).

Pressure should be held for approximately 5-10 minutes for radial or brachial artery punctures and 20-25 minutes for femoral artery punctures. Light pressure should be held for a few additional minutes once hemostasis is achieved to decrease risk of re-bleeding.

While compression is being applied, the distal pulse should be checked every 2 to 3 minutes to ensure circulation. Thereafter, monitoring for bleeding and distal circulation is based on facility policy.

There are a few things to note here.

- To avoid complications, occlusive pressure should not be applied to the puncture site for more than 3-5 minutes. After 3-5 minutes of full pressure, reduce to 75% pressure for 3-5 min, 50% pressure for 3-5 minutes, and 25% pressure for 3-5 minutes.

- In patients who have a coagulation disorder, are on anticoagulation therapy, or when a larger sized catheter was used, it may be necessary to apply pressure at the puncture site for a longer period of time.

- Patients who have had diagnostic or interventional catheterization may be required to maintain bedrest for 4-6 hours after the procedure.

- There are a number of vascular closure devices (VCDs) and hemostasis pads available to facilitate hemostasis, and several compression devices that can be used to provide mechanical compression.

Qualified Clinicians

Ensuring that the procedure is performed by well-trained, qualified clinicians reduces complications associated with arterial punctures. A variety of qualified healthcare professionals perform arterial punctures, and, depending on state specific scope-of-practice laws and facility policy, this may include RNs who have completed training and demonstrated competence in arterial puncture or arterial line placement.

However, it remains the purview of the medical practitioner, i.e., the interventional cardiologist, radiologist, or endovascular surgeon performing the percutaneous procedure to establish vascular access.

Okay, now that we’ve gone over the process, let’s look at a few review questions.

Review Questions

1. Site selection for arterial puncture is extremely important. Which of the following statements best describes factors considered in choosing the optimal puncture site?

- Purpose for the puncture, preference of the clinician, patient’s hand dominance, availability of fluoroscopic guidance to aid vascular visualization, size of the artery and needle.

- Purpose for the puncture, ability to locate the artery; patient’s clinical status, history of recent surgery and hand dominance.

- Purpose for the puncture, size of the artery, ease of access, patient’s clinical status, including history of recent punctures, previous peripheral vascular surgery, the presence of infection at the site.

- Purpose for the puncture, ease of access, patient’s clinical status, availability of fluoroscopic guidance to aid vascular visualization, catheter dimensions, and patient’s hand dominance.

2. Arterial punctures are not risk-free. Which of the following statements best describes how to reduce the risk of complications?

- Selection of the most optimal puncture site, adherence to aseptic technique, appropriate positioning techniques, proper insertion technique and adequate post procedural hemostasis.

- Selection of the most optimal puncture site, adherence to aseptic technique, proper insertion technique, adequate post procedural hemostasis, and early recognition of complications.

- Selection of the most optimal puncture site, appropriate positioning techniques, ensuring only the physician performs the procedure and adequate post procedural hemostasis.

- Selection of the most optimal puncture site, adherence to aseptic technique, adequate post procedural hemostasis, prompt diagnosis and appropriate treatment of complications.

3. Which of the following statements is not true?

- Arterial punctures for continuous monitoring of blood pressure (IAP), minimally invasive diagnostic procedures, and to obtain arterial blood samples are performed by RNs with specialized training.

- After the puncture, the clinician (not the patient) should apply firm direct pressure at the puncture site. It may be necessary to apply local pressure for a longer time for patients who have a coagulopathy or are on anticoagulation therapy.

- Complications can be minimized by selecting an optimal puncture site, adhering to aseptic technique including antiseptic skin prep, appropriate positioning, achieving adequate post procedural hemostasis and ensuring those who perform the procedure have been trained and demonstrated competency.

- Complications which can occur during or after the procedure include: artery vasospasms, arterial dissection or occlusion, pseudoaneurysm, access site bleeding, hematoma, and trauma to adjacent structures.

I hope this review was helpful! Thanks for watching, and happy studying!

- “Minimally Invasive Heart Surgery.” n.d. Temple Health.

- “ASEPTIC NON-TOUCH TECHNIQUE -OLCHC Reference Guide.” n.d.

- “Arterial Puncture.” n.d. TheFreeDictionary.com

- “Prevention Strategies.”

- Bhatty, Shaun, Richard Cooke, Ranjith Shetty, and Ion S Jovin. “Femoral Vascular Access-Site Complications in the Cardiac Catheterization Laboratory: Diagnosis and Management.” Interventional Cardiology 3 (4): 503–14

- Brown, Kristen N, and Nagendra Gupta. “Percutaneous Transluminal Coronary Arteriography.” Nih.gov

- Carleton, Steven. “Taming the SRU.”

- “Shibboleth Authentication Request.” 2023

- “Arterial Puncture.” n.d.

- “Chapter 14: Arterial Puncture Procedures Objectives Objectives.” n.d.

- “A Perspective on Sheath Selection and Access Sites for Coronary Angiography.” n.d. Cath Lab Digest

- “Arterial and Venous Access and Hemostasis for PCI.” Thoracic Key

- Radial Access for Peripheral Vascular Procedures.” Endovascular Today.

- Noori, Vincent J., and Jens Eldrup-Jørgensen. 2018. “A Systematic Review of Vascular Closure Devices for Femoral Artery Puncture Sites.” Journal of Vascular Surgery 68 (3): 887–99

- Reich, David L., Alexander J. Mittnacht, Martin J. London, and Joel A. Kaplan. “Monitoring of the Heart and Vascular System.” Essentials of Cardiac Anesthesia, 167–98

- “Femoral Arterial Access and Complications.” The Cardiology Advisor

- Grabau, Danny, and Randy Gruhlke. n.d. “Arterial Punctures Blood Gas Collections (ABG)”

- Hill, Steve J. 2019. “Avoiding Complications during Insertion,”

- “Neurological Interventional Radiology | Houston Methodist.” n.d.